"All surface life depends on life inside and beneath the oceans. Sea life provides half of our oxygen and a lot of our food and regulates climate. We are all citizens of the sea."

~ Ian Poiner, chairman of the Census of Marine Life Steering Committee

Image source: Census of Marine Life

Bluefin tuna from the Mediterranean at the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo.

(Image credit: Toru Hanai/Reuters)

Some of the marine life discovered is so exotic, so lushly beautiful, that it takes your breath away. You can see some of the images at the Census gallery. Some of the creatures are mysterious and truly bizarre-looking. And some live in conditions as inhospitable as any on this planet. The report, the galleries, and some of the perspectives that have been offered on the Census are truly enthralling to anyone who loves the sea, or loves interesting creatures.

My excitement is, however, tempered by the fact that several months ago, one the Comtesses sent me some info about Paul Greenberg's forthcoming book, Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food, which I then devoured, and if you'll excuse a further pun, stewed on. Greenberg is a regular contributor about marine life, seafood and marine environmentalism at the New York Times. This book, along with a harrowing series of articles in the Times, gives me serious pause for thought about the riches and diversity that are revealed in the Census of Marine Life report.

When you consider Greenberg's op-ed piece on menhaden, published last December, you can get a feel for how very fragile our understanding is of the collective marine ecosystem. Menhaden, a very small forage fish, are filter feeders. They keep our oceans clean and provide food for larger predatory fish. At least one author, H. Bruce Franklin Ph.D., has called menhaden The Most Important Fish in the Sea. Drastically overfished for use as lubricants, and ironically as food for farmed fish, the menhaden is rapidly disappearing from the Eastern seaboard, and as a result, the bass population in Chesapeake Bay has been heavily impacted. Other impacts include the fouling of water and creation of large dead zones.

"The muddy brown color of the Long Island Sound and the growing dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay are the direct result of inadequate water filtration — a job that was once carried out by menhaden."

~ Paul Greenberg, A Fish Oil Story, New York Times

On the other end of the size spectrum, we can look at endangered bluefin tuna, a huge fish. Bluefin is one of the Four Fish. (The other three are sea bass, cod and salmon) In a long article in the NY Times Magazine, Greenberg talks about Tuna's End. Overfishing of tuna, and lack of a consistent international approach to tuna fishing, has devastated most of the bluefin population. And yet, the market still demands and receives wild caught bluefin.

Bluefin tuna can reach a length of more than ten feet and weigh in at more than a thousand pounds, though tuna of that maturity and size are almost never seen now in the wild. Swimming in the frigid arctic, the Northern Bluefin tuna, uses thermoregulation to prevent heat loss and permit more efficient muscle functioning. That's right, we're talking effectively warm-blooded. Their countercurrent exchange of blood provides them with the ability to swim and feed in ice cold water, in a fashion relatively unique in the fish world. This magnificent fish is now critically endangered.

I don't know about you, but I'm a big lover of sushi. My diet, as many of you know, is rather limited by intolerance and auto-immune problems. Pure protein, like that in sashimi, is always a pretty safe bet for me. And I love(d) toro. But I won't eat a critically endangered fish like bluefin. As Treehugger.com says, "you wouldn't eat a tiger, so why would you eat endangered bluefin tuna?"

But here's the thing. You know those little charts that you can get from the Monterey Aquarium people that tell you what's environmentally moral to eat (I mean, that's what they're really trying to tell you, right?) and what's not? Do you ever wonder if they, or the principles on which they are based, really work? I even have the Bay Aquarium's neat little app on my iPhone (which I still shudder to think about in light of the whole Congo business, let me tell you). It has recommendations for seafood and sushi. Most everything that I used to eat is on the avoid list. But what does it mean when we then switch to new fish to decimate? Because if we all start eating tilapia instead of tilefish, we'll soon end up with the same problem we had with tilefish. Our human numbers on this planet, and the first world's wherewithal to purchase wild fish, will soon knock down any species numbers. Look at what we've done with menhaden, which had been the most plentiful fish in the world. The global catch of wild fish in 2009 was estimated to be 170 billion pounds a year. (As Greenberg says, it's equivalent to the net weight of the entire population of China...)

So should we eat wild fish at all?

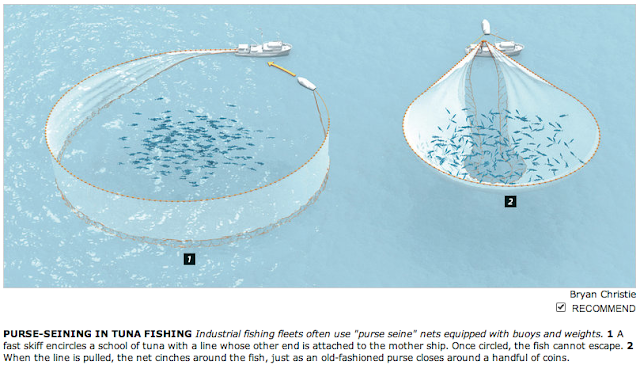

If you listen to Paul Greenberg, the disequilibrium in our oceans is getting to the point where really, in good conscience, we probably shouldn't eat wild-caught fish, especially not caught in any mass fishery kind of way like with purse-seining.1 And, of course, we shouldn't be fishing menhaden into extinction, for lipstick and fish oil, either. Farmed fish is it's own kind of problem, of course. From pollution to antibiotic use, to the potential escape of farmed fish into the ecosystem, farmed fish are not a facile solution by any means. But they may be our only solution.

Of course, fishing is not the only thing that impacts marine life. There are all the dams that affect salmon, and oil spills like the Deepwater Horizon. You have only to read the little horror story of the BP coverup over at Mother Jones, to see the devastating long-term effects of oil plumes on marine life in the deep scattering layer (oil has spread down into the even the abyssopelagic zone, of which there are a few areas in the Gulf of Mexico). I seriously considered blogging about that article last month. It is so depressing (and that's compared to what I normally blog about, so you think about that, people...) and so complex, that I really didn't know if my readers would want to hear about it. There's so much land drama can we take more marine drama now that the spill is supposed to be capped?

But today's article and the release of the census stirred me to write about the issue of fish and marine life. Or more precisely, it was Ian Poiner's quote at the top of this article. Most of my readers know Rachel Carson's sentinel book The Silent Spring. We now hover on the 60th anniversary of her National Book Award winning The Sea Around Us. (In some respects, Greenberg, with his reverence for the oceans and marine life, seems almost to be channeling Carson with his temperate warning of impending environmental disaster.) Our oceans are in such a state of crisis. It is so very sad.

Scientists have spent ten years cataloguing such magnificence.

How on eaarth2 are we going to save it?

1Purse-seining, by Bryan Christie, from the New York Times article Tuna's End:

.jpg)

FAIR AND BALANCED!

ReplyDelete________________

dissidentphilosophy.lifediscussion.net/art-f6/the-boobquake-911-t1310.htm

And finally, the *only* man in Minnesota who says there is no God has suddenly become an arbiter on mental health...

I actually was a salmon fisher in Alaska at one point and my family there still depends on it, both purse seining and gillnetting.

ReplyDeleteThis problem really is an international problem. Alaska has done many things (especially since the 1980s), some significantly impacting people who fish, to ensure that the forms of sea life it allows to be caught are sustainable.

Scientists monitor all Alaskan streams carefully for salmon escapement each year and the data they collect is used to determine if a fishing period stays open, where it is located, and what kind of fishing is allowed (including sports fishing in the rivers). The thing is, Alaska has no control over what happens to sea creatures when they leave state waters.

As someone intimitely tied to the Alaskan fishing community, I vehemently abhor farmed salmon. It is simply another tool of megacorporations to make a quick buck with little regard for the wild marine life it replaces or the rural communities they destroy. What I want to say is that traditional fishing of wild marine life is sustainable IF people move to protect marine wildlife from overfishing (in rivers and on the ocean), pollution, and farmed fishing.

As for bluefin tuna and sushi, not all tuna sushi is necessarily bluefin tuna, and I think both the media is failing to do its job to distinguish bluefin from other tuna and that there should be a legal requirement for the kinds of fish served in restaurants to be named by type of fish and area caught or farmed. I can't count the number of times I have specifically requested wild caught Alaskan salmon and been given farmed Atlantic salmon by clueless staff. I have recently tried the same thing with tuna by asking them if it is bluefin and guess what, nobody knows! This should not be happening. Seafood needs better labeling regulations at the federal level.

Thoughtful commentary, Aratina.

ReplyDeleteI'm uncomfortable with the idea of farmed fish, I have to say. First, I don't think they are farmed in healthy conditions (for them or for us) and then we get into the whole issue of what it is like for almost any even remotely sentient animal that is farmed in this country.

I'm totally with you on the tuna sushi part. I think toro was almost exclusively bluefin (occasionally yellowtail) but a lot of what is served now is more likely bonito or skipjack tuna, which is more abundant, though not really thunnus species.

Interestingly, the Monterey Bay Aquarium chart lists Alaska wild-caught Salmon as a 'Best Choice' on their chart, with Oregon Salmon as a 'Good Alternative'.

Of course, if we all start asking for those, that situation won't hold out either. As my husband says all the time, the real problem on this planet is that we are just far too many people. :(

"Of course, if we all start asking for those, that situation won't hold out either."

ReplyDeleteYes, that used to be a problem until the scientists started getting involved in the salmon industry. Now, if the number of salmon returning upstream is not within an acceptable range, the state fisheries board can shut down all salmon fishing indefinitely without respect to the economic demand. Alaska has learned the hard way about that with many of their wildlife species, but it is getting to the point where almost everything is regulated to prevent over hunting and overfishing. They even take subsistence fishing and hunting into account when considering the total catch or bounty. For commercial and sports salmon fishing, a high demand would be most welcome by the people whose livelihood depends on fishing ( I can say that with near certainty! :) ) and the salmon would in theory be protected as a species from overfishing by the regulatory board.

Another thing is that Alaska actually plans ahead for the commercial and sports catches by hatching more salmon than the rivers can take, so an end to commercial and sports fishing due to low demand caused by salmon farming carries the risk of being devastating to the salmon population as well. In a lot of ways, the salmon industry was lucky because some of the other fisheries in Alaska did get overfished in the 1980s before regulations were put in place and the affected species were nearly wiped out and are still struggling to make a come back (these include halibut and king crab).

What do you make of the fact that other countries do not abide by the same practices, however? Salmon provide a unique situation because they spawn in US territory. The issue for many other fish is less enforceable, at least in a consistent way, it seems.

ReplyDeleteDid you know that actually Pacific Halibut is considered a 'Best Choice' on the Monterey Bay Aquarium list? (As opposed to Atlantic Halibut, which they list as an "Avoid". They've been reading this post btw, according to my IP address tracker...) Wouldn't that include Alaska's Halibut, then? If they were fished into the critically endangered or vulnerable range, why say "Best Choice" I wonder?

Several people have written to me asking me to put up lists or links to lists of the fish that are safe/morally responsible to purchase or eat in restaurants.

I don't even begin to know what to tell them.

So many times in fish markets you see that things don't really come from where they say they do. And I doubt restaurants will be any better than that... :(

"If they were fished into the critically endangered or vulnerable range, why say "Best Choice" I wonder?"

ReplyDeleteI remember seeing the size of the halibut begin to decline, but it could have been a false impression; they might not have been endangered in the short term. I can't imagine the hit the halibut population took during fishing season was beneficial for their continued survival, though.

The way they used to fish halibut was an all-open period with no catch limits. The period itself kept shrinking, and I have assumed this is because they were catching too many halibut and that was the only way to reduce the catch at that time (which I can't confirm, but I did find a similar sentiment on page 2 of this PDF). Regardless, the practice was not only a danger to the fish but to the people fishing--they would keep going for days on end (hooks flying all about) without sleep no matter what the weather was like to make their money. That practice was ended in favor of an annual quota system (see here and for the initial reaction, here), which reduced the stress on both the fishing community and most likely the halibut population.

So, halibut are probably considered "best choice" today because there is much less chance of them being overfished due to the quota program.

Yeah, I shouldn't have grouped halibut with king crab up there, but I did get the impression that the halibut being caught prior to the implementation of IFQs and just after were of a smaller size than they were back in the days of the free-for-all kind of halibut fishing, and I had believed it was because they had been overfished. I saw the same thing happen to razor clams, which were enormous creatures until all of Anchorage it seems found out about them and went off to the beaches to dig them, as you warned of in your comment above.

ReplyDelete